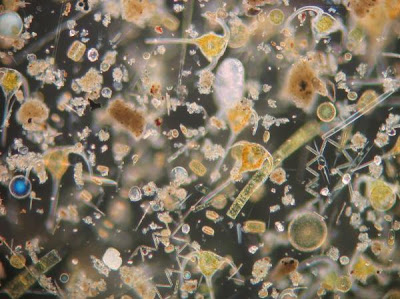

Researchers have been continuously talking about the declining of planktons. Have you ever spared a though about why has this been happening? The mystery is revealed here! Just as recently as January 12 2009, a report from ScienceDaily says that the history of the evolution of diatoms -- abundant oceanic plankton that remove billions of tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through out each year -- requires to be brought in the light, according to a new Cornell study. the study spans back to some 33 millions ago, when an abrupt rise in the number of species, there was a sudden fall of diatoms -- trends that coincided with severe global cooling. According to the research, the long-held theory that diatoms' success was tied to an influx of nutrients deep into the oceans from the rise of grasslands that had taken place some 18 million years ago is doubtful enough to be true. From the recent study, led by graduate student Dan Rabosky of Cornell's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, the researchers got an evidence of a much widespread problem in paleontology: that older fossils are harder to find than the younger ones.

Researchers have been continuously talking about the declining of planktons. Have you ever spared a though about why has this been happening? The mystery is revealed here! Just as recently as January 12 2009, a report from ScienceDaily says that the history of the evolution of diatoms -- abundant oceanic plankton that remove billions of tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through out each year -- requires to be brought in the light, according to a new Cornell study. the study spans back to some 33 millions ago, when an abrupt rise in the number of species, there was a sudden fall of diatoms -- trends that coincided with severe global cooling. According to the research, the long-held theory that diatoms' success was tied to an influx of nutrients deep into the oceans from the rise of grasslands that had taken place some 18 million years ago is doubtful enough to be true. From the recent study, led by graduate student Dan Rabosky of Cornell's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, the researchers got an evidence of a much widespread problem in paleontology: that older fossils are harder to find than the younger ones.Rabosky said that they tried to address the simple fact that the number of available fossils is colossally greater from recent times than from earlier times. He added, "It's a pretty standard correction in some fields, but it hasn't been applied to planktonic paleontology up till now." Over 90% of the diatom fossils that are known, are younger than 18 million years. Another unadjusted survey of diatom fossils has given a clue of the fact that more diatom species have been in existence in the recent past than just 18 million years ago. Researchers say that it is possible to understand the dearth of the early fossils. In order to get the sampling for the diatom fossil, drill ships are required to be bored deep into sea floor sediment. The scientists needs to find out the ancient sediment on the seafloor first in order to find a trace of an ancient fossil, which is not an easy job, because plate tectonics constantly shift the ocean floor. Fossils spots are also shifted as a result. Moreover the great part of the seafloor is to young to sample, as per the scientists.

While making the research, Rabosky and co-author Ulf Sorhannus of Edinboro University of Pennsylvania controlled for the number of samples that were taken from the time period of each million-year of the Earth's history, going 40 million years backward. Re-analysis of the findings, caused that long-accepted boom in diatoms theory over the last 18 million years simply disappear. Instead of that long-accepted boom in diatoms theory, the researchers concluded that there had been a recent gradual rise, with a much more dramatic increase and decline at the end of the Eocene epoch, that is, about 33 million years ago.

The diatoms gained their peak diversity at least 10 million years prior to when grasslands became came into being. Rabosky said, "if there was a truly significant change in diatom diversity at all, it happened 30 million years ago". According to him, "the shallow, gradual increase we see is totally different from the kind of exponential increase you would expect if grasslands were the cause". While giving an example of an increase of that type, Rabosky recalled another fossil record -- the teeth of horses. Before the grasslands came into being, the horses were believed to have smaller teeth that were suited for chewing soft leaves... not the harder grass like today. This belief had been supported by scientific researches. As per Rabosky, although the diatoms ought to have shown a similar evolutionary response to the sudden availability of silica, yet they don't.

The diatoms gained their peak diversity at least 10 million years prior to when grasslands became came into being. Rabosky said, "if there was a truly significant change in diatom diversity at all, it happened 30 million years ago". According to him, "the shallow, gradual increase we see is totally different from the kind of exponential increase you would expect if grasslands were the cause". While giving an example of an increase of that type, Rabosky recalled another fossil record -- the teeth of horses. Before the grasslands came into being, the horses were believed to have smaller teeth that were suited for chewing soft leaves... not the harder grass like today. This belief had been supported by scientific researches. As per Rabosky, although the diatoms ought to have shown a similar evolutionary response to the sudden availability of silica, yet they don't.The new findings fail to explain the diatoms that are currently prevalent in the ocean, yet Rabosky said that whatever led to the rise in diatoms' at the end of the Eocene period, the tiny organisms may have contributed to a greater extent to the global cooling that followed. Rabosky said, "why diatom diversity peaked for 4 to 5 million years and then dropped is a big mystery. But it corresponds with a period when the global climate swung from hothouse to ice house. It's tempting to speculate that these tiny plankton, by taking carbon dioxide out of the air, might have helped trigger the most severe global cooling event in the past 100 million years"

Rabosky's research has been partly supported by the National Science Foundation.

Comments